INTERVIEW WITH GONZO LAWYER HAL HADDON

INTRODUCTION BY ANITA THOMPSON

We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold. I remember saying something like “I feel a bit lightheaded: maybe you should drive…” And suddenly there was a terrible roar all around us and the sky was full of what looked like huge bats, all swooping and screeching and diving around the car, which was going about a hundred miles an hour with the top down to Las Vegas. And a voice was screaming : “Holy Jesus! What are these goddamn animals?” Then it was quiet again. My attorney had taken his shirt off and was pouring beer on his chest, to facilitate the tanning process.

HUNTER S. THOMPSON, FEAR AND LOATHING IN LAS VEGAS

Yes. The freedom Hunter expressed in life and in every line of his work was often made possible by the longtime friendships he cultivated with his attorneys. Starting the tradition was of course Oscar Zeta Acosta, the famous “Samoan” attorney (Hunter originally used that term to hide Oscar’s identity) who for years counseled Hunter on everything from how much mescaline should be eaten to what never to say to a police officer to morale boosters when Hunter ran for Sheriff of Pitkin County in 1971 on the Freak Power ticket.

The list of Hunter’s lawyers grew rapidly over the years following Oscar: John Clancy, Michael Stepanian, Gerry Goldstein, Abe Hunt, John Van Ness Keith Stroup, and on criminal lawyers such as George Tobia, Joe Edwards, and Morris Dees.

Hal Haddon is not the sort of lawyer you will find speeding shirtless down the highway pouring beer on his chest. No. Hal was Hunter’s lead attorney for other reasons. They share the blood of a tribe that started perhaps around Bobby Kennedy and Chicago in 1968 (they finally met in 1974) and spans the decades of political victories and losses ever since. The blood of this tribe runs thicker than money or whiskey and is the only reason I can fathom why Hal had defended Hunter like a lion with the full force of his law firm before and after his death and never charged a dime.

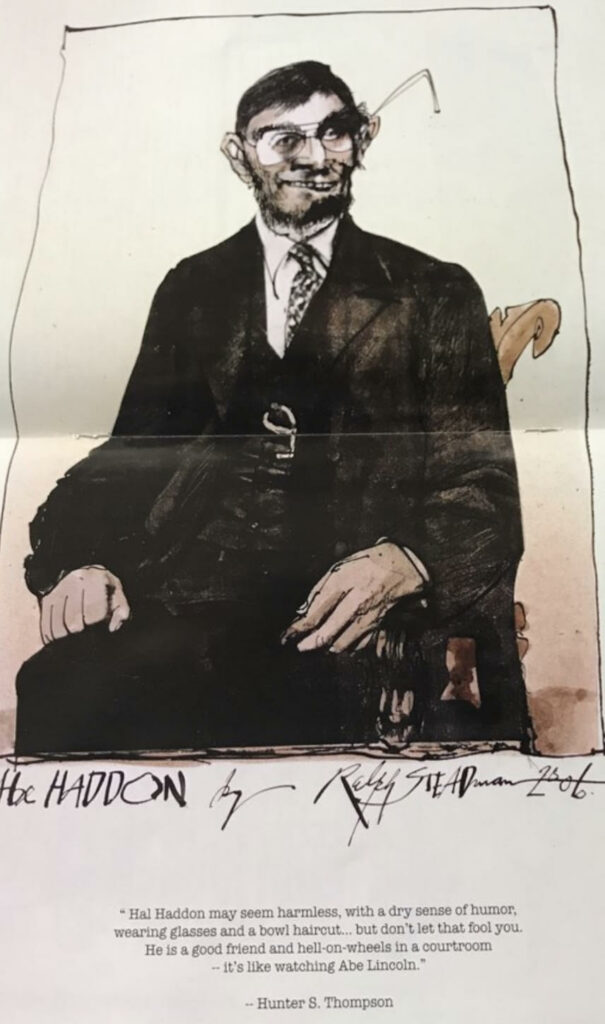

Years ago, right before Hunter introduced us, he wrote Hal’s phone numbers on a small piece of yellow paper and told me to always keep it in my wallet. Then he said something like, “Haddon may seem harmless, with a dry sense of humor, wearing glasses and a bowl haircut, but don’t let that fool you; he is a good friend and hell-on-wheels in a courtroom — it’s like watching Abe Lincoln.” I understood.

So now I’m happy to share with you my interview (Kitchen-style conversation at the Crawford Hill Mansion in Denver) with our friend and attorney, Hal Haddon.

ANITA THOMPSON: Thanks for talking with me. You rarely give inter-views, so this is a treat. First, let me ask you a little bit about your background. You were born in Flint, Michigan?

HAL HADDON: I was born in Flint, Michigan, home of Michael Moore, on December 2, 1940.

AT: How about your parents? Do you have brothers and sisters?

HH: My father was a farmer. He is now 91 years old. He is still farming in a little town south of Flint called Holly. My mother was an actress; she did summer stock and local plays. I have a brother who has a Ph.D. in education and lives in Portland, Oregon, and commutes to Spain because he teaches Spanish as well as general education.

AT: Your father is still working?

HH: My father gets on a tractor every day and goes out in the field. He actually runs a nursery now. He has a number of employees that handle the nursery. But he goes out and motors around and trims trees, and chases fish.

AT: Is he the one who taught you to fish?

HH: No, I’m self-taught. He is more of a bait fisherman. He has a lake on his farm; he goes out on a boat. I’m a stream fisherman: I wade and I fly-fish.

AT: How did you get turned on to fly-fishing?

HH: I actually was rowing a boat around when I was in high school and some guy with a fly rod gave me five bucks to row him around the lake. He was catching a lot more fish with his fly rod than I was with worms. So that changed my life. There is a metaphor for that — success requires as much art as effort.

AT: What got you into criminal law? What turned you on to law in the first place?

HH: What got me to law school was that I was trying to avoid the draft. I didn’t, by the way. I ended up serving.

AT: In the Air Force?

HH: I started out in the Air Force and then I transferred to the Navy JAG [Judge Advocate General] after I got my law degree. But I went to Duke to law school in 1963 which was the start of the Vietnam War. I graduated in 1966 and came to Denver.

When I came to Denver I got hired by one of the big corporate law firms in town. But big in those days was fifteen to twenty lawyers — not a thousand like it is today. I started out in a law firm called Davis, Graham, and Stubbs, which was “Whizzer [former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Byron R.] White’s” old firm. I did that for about four years. It was valuable because I learned how to be a careful lawyer, but I didn’t meet any human beings. I just wrote briefs; I didn’t find it very satisfying.

So in 1970 the Colorado Public Defenders system was first established. There was no public defenders’ system in Colorado before 1970. When it was established, I went to work as one of the first public defenders. I got through several hundred trials and really learned the criminal process and never looked back.

AT: When you were in law school did you intend on being a criminal lawyer?

HH: No, I had no idea what I was going to do. I intended not to go to war.

AT: And you did go to war.

RH: Yes, I did go to war anyway — but as a lawyer. My gun was a briefcase.

AT: So the public defenders’ office did change your life. Is that when you came up with the slogan “Reasonable Doubt for a Reasonable Fee?”

HH: No, that came when I started charging fees. You can’t charge fees when you’re a public defender. I was in the defenders’ office until 1974. Then I managed Gary Hart’s campaign — his first Senate campaign — in 1974. After that I went into private practice. Brian Morgan and Lee Foreman and I started this firm in 1976. When we started charging money, we wanted it to be reasonable (smiles).

AT: How did you get involved in politics and with Gary Hart?

HH: In 1968, when Robert Kennedy decided to run for president, I volunteered for his campaign and I was on his advance team — I was an advance man for Kennedy in ’68. Gary Hart was one of the regional organizers. So I met him in the Kennedy campaign and we became pretty good friends. He managed McGovern’s campaign in ’72, and that’s how he met Hunter. Because I was at the public defenders’ office I couldn’t do political things, but when [Hart] decided he wanted to run for the Senate in ’74, he asked me to manage the campaign. I was dumb and happy and thought I could do anything even though I had no experience at it, and I did it. That’s how I got involved in politics.

AT: Was it Senator Hart who introduced you to Hunter?

HH: Here’s how it happened. Hunter was THE best political writer in the ’70s, in my view. I loved his stuff. I come from a whole tribe of political junkies who used to run out and grab Rolling Stone every issue just to read Hunter.

I told Hart, after we won the election in November of 1974, when he asked me what I wanted — because he hadn’t paid me, because we didn’t have any money — I said, “I want to have breakfast with Hunter Thompson.”

And so he set it up. We did it at the Oxford Hotel in Denver. Of course, Hunter didn’t show up for breakfast until four in the afternoon. Hart and Hunter and I spent a couple of hours drinking and having a late breakfast, and Hunter and I became very good friends after that.

AT: What was your first impression of Hunter?

HH: My first impression was absolute awe — that this guy could drink three or four bloody marys and three or four scotches and snow cones and a couple of beers and eat huevos rancheros. and function . . . And he did alI that in about two hours.

AT: What was it like representing Hunter in court? Or representing him in general?

HH: (chuckling) The reason that Saskia [Jordan] and [Gerry] Goldstein would come along was just to control Hunter. When you’re a defendant in court, you’re supposed to sit there and listen and take it. That really wasn’t Hunter’s style. So Saskia would sit on one side of him and Goldstein would sit on the other and whisper at him, write him notes, pull him down, make sure he didn’t have whiskey his water glass: sometimes he did.

The biggest challenge in representing Hunter was that you’d wake up in the morning and read the daily newspaper and Hunter would have told them what our strategy was. You’d kind of like that to be a surprise. But Hunter, being a journalist, wanted to tell the world what we were going to do in advance. As a lawyer that is just . . . uncomfortable.

AT: Did you ever tell him not to?

HH: Sure! I always told him not to.

AT: He just didn’t listen?

HH: Oh, he listened. He just did what he wanted to do. Hunter always listened.

AT: Interesting . . . Keith Stroup tells a great story about how there was a time when he and Gerry were investigating other options because they were sure that Hunter was going to be convicted. You were the one that said, “A) Don’t ever utter something like that to Hunter, and B) We are not going to lose this one.” Were you the one that . . .

HH: I always thought that in Aspen it was a triable case, that we had good Fourth Amendment issues, and I had no idea until I got her on the stand how BAD the complaining witness was. That won the case. But you never know until you see the evidence.

IT IS TRUE THAT THE CLASS OF PEOPLE THAT WILL RUN FOR PUBLIC OFFICE, I THINK, HAS BEEN SERIOUSLY DOWNGRADED. AND THAT IS BECAUSE THE PROCESS HAS GOTTEN SO NASTY. POLITICS HAS ALWAYS BEEN A CONTACT SPORT. BUT IT WAS NEVER AS VICIOUS AND PERSONAL.

AT: She was the one that was flirting with Hunter on the stand.

HH: Yes. She got up on the stand, and after she was sworn, she waved at Hunter and said, “HI, HUNTER!”

AT: (laughing): That’s beautiful. It must have been fun.

HH: (speaking softly): Actually, that preliminary hearing was as good as it gets. But you never know that going in.

AT: Speaking of fun, what is it like being an executor of the Thompson estate?

HH : (smiling) You really want to ask me that question?

AT: Yes, I really do.

HH: It has taken about half of my time for the last fifteen months. What I do is organize the archive, which is very difficult, and value both Owl Farm and the archive. Putting together all of that information has been very time consuming, so I’d have to say that “painful” is the word. But I am happy that we’ve been able to manage it in such a way that Owl Farm is still Owl Farm and that you are still living there and that Juan can go there. Hopefully, if you want to stay there, we can perpetuate that.

AT: Yes, indeed, I will stay. So anyway, you don’t regret agreeing to be an executor, right?

HH: (laughing) Never. Never regret. Never look back.

AT: Good. I’m glad you agreed to be a trustee, and I’m glad you’re still on board and I’m glad you don’t regret it . . . Any regrets about Gary Hart’s campaign?

HH: I don’t have any about the campaigns until 1987. I have a lot of regrets about 1987. Hart would have been a great president. But he made a great mistake. It changed the course of history, in my view. I think he would have won.

AT: Hunter thought the same thing. Why do you think he would have made such a good president?

HH: He is enormously thoughtful and experienced in matters having to do with world affairs. He was a very committed — I wouldn’t say environmentalist, but steward of the land — a very bright, very thoughtful, very substantive guy . . . Instead, we got four years of Bush. And disappointing Supreme Court justices, but they weren’t as bad as the current Bush’s appointments. But Hart’s appointments would have been more progressive. Events would have been much different.

AT: We wouldn’t be at war?

HH: Well, I don’t know what we would be doing today, but we’d have one less Bush we’d have to suffer.

AT: You told me once that you thought that Michael Tigar and Hunter Thompson were the smartest of all your friends.

HH: I think that’s true. I would put Gary Hart in that category, too. They’re brilliant for a lot of reasons: their absolutely stunning range and their ability to put things in words.

AT: Can you tell me something specific about your relationship with Hunter, or what really set him apart from others? How about his knowledge of the law?

HH: Well, he was a connoisseur of the law, but he needed to be, given his life-style. He was a very astute judge of law-yers, and he was a very astute judge of his legal situations. The part of Hunter that I value the most was the political miscellanea. He was enormously insightful about politicians.

AT: Jimmy Carter’s chief of protocol gave a dinner for Hunter in Hawaii-when he was the president of the University of Hawaii — and he stood up and said, “I just want you to know that Jimmy Carter would never have been president if it weren’t for Hunter Thompson.”

HH: There’s a lot of truth to that.

AT: A lot of people say that. You told me once why you didn’t have children. Would you mind elaborating?

HH: (laughing) I’m not sure what my excuse was then.

AT: Because you work so hard.

HH: That’s a lot of it. I am, in my professional life, twenty-four/seven. And I don’t think that I could have done a very good job professionally if I wasn’t that manic and Type-A about it. But I didn’t think I could do justice to both the profession and to children. And my wife was also a professional and felt the same way.

AT: You’re lucky to have a wife that felt the same way.

HH: I am lucky we felt the same way. I don’t really regret it. I’ve had a great career. But it’s a matter of self-knowledge. If you can’t do justice to kids, you shouldn’t have them.

AT: That’s another reason why I think you should run for the U.S. Senate.

HH: (laughing) Because I have no kids, I’ve got time?

AT: Exactly. Well, we’ll get to that . . .

HH: I’m supporting Mark Udall, you know.

AT: Yes, yes I know. I’ve been doing some research. He’d make such a great governor, and that way he could go on to run for president. It’s difficult to run for president as a senator, correct?

HH: Well, he talked about running for governor, but he didn’t do it.

AT: But what if [Democrat Bill] Ritter loses?

HH: If Ritter loses, then we have four years of [Republican] Beauprez.

AT: Right. Then Udall could run for governor in four years.

HH: He could, but I don’t think he will. His family has a long tradition of national politics. When I say national, I’m talking about congressional politics. And I think that is really the culture that he understands, and he does a great job.

AT: He’s so young, though. He’s only 56.

HH: ONLY? You think that’s young? l do too!

AT: That’s too young to be a senator.

HH: Hart was — when he was first elected — I think he was 38.

AT: Well, it was different then.

HH: You’re right.

AT: The average age of a senator right now is 57. And it shows.

HH: Strom Thurmond is gone. He probably dragged the average up.

AT: McCain is 69, and he’s running for president.

HH: Reagan was in his seventies.

AT: And they are very good thinkers.

HH: Yep.

AT: And your dad is 91 and . . .

HH: He is 91 and has got a great mind.

AT: See? I don’t know why you resist this so much — the whole senator thing. There are so many people who would want you to run.

HH: You’re the only one I know of.

AT: Really? No! That’s not true. Any person ever represented by you and certainly Woody Creek would . . .

HH: No, it is true.

AT: Well, what if Gary Hart and George McGovern asked you to run? I spoke to George McGovern yesterday. He is such a gentleman; he called to ask if I need-ed help with anything. And l said, “Yes, there is …. Senator … “

HH: (laughing) First of all, they won’t. I know Gary supports Udall. I think my time has passed. I thought about it when I was asked seriously to run for governor in the ’80s. I thought about it and didn’t do it. I didn’t do it because I’m a private person … and I have a profile as a criminal defense lawyer. Although I’m proud of what I do, I don’t think the public values criminal defense lawyers very highly. I’ve done some high-profile cases that are controversial.

AT: I don’t know …. We’ll have to reassess all that later.

HH: I’ve assessed it. I’ll tell you what I said when I told people I wouldn’t run for governor: “I seriously considered it, and I seriously rejected it.”

AT: But you already spend quite a bit of time in Washington. What do you do there?

HH: In Washington, I sit on the ABA Criminal Justice Standards Committee, which has just completed a comprehensive set of standards for DNA laboratory procedures and a suspect’s right to access DNA evidence. ABA Criminal Justice Standards are developed in a lengthy collaborative process with judges, prosecutors, and scientists. They have a high degree of credibility in courts around the country and in Colorado. These standards will improve the quality of DNA testing and provide open access to DNA testing by persons who may wrongfully accused or convicted.

AT: That’s what I mean: you’ve been working so long and hard at politics, to make this world a better place. And right now it is so ugly what is happening in the Senate, and to our Bill of Rights, and all the people of Colorado could be your client if you were our Senator. But you refuse.

HH: You know, it is true that the class of people that will run for public office, I think, has been seriously downgraded. And that is because the process has gotten so nasty. Politics has always been a contact sport. But it was never as vicious and personal.

AT: Hunter helped make it personal.

HH: Yeah, Hunter made it personal. But it was never as bad in those times as it is presently. It’s just poisonous.

AT: It seems like bad news.

THE MEDIA ALWAYS WANT TO GIVE IT ALL OUT BEFORE A TRIAL BECAUSE THEY WANT TO BE FIRST, AND THAT CAN HAVE THE EFFECT OF POISONING A JURY — POISONING YOUR CHANCE TO GET A FAIR TRIAL.

HH: It is bad news. I mean it needs to change. And there are some practical people around who talk about it a lot, such as the negative ads and the need to change, but they’re not going away.

AT: You spoke a little bit in your lecture at the NORML conference about the Sixth Amendment. Do you think that is a risk right now — the weakening of the Sixth Amendment?

HH: The Sixth Amendment says that you have a right to a fair trial and you have the right to a compulsory process. What I was talking about at the NORML conference was the media, and the media basically claim that the First Amendment is better than the Sixth: it trumps it, and that is a constant tension because the media want access to everything before a trial. I believe that for a trial to be truly fair, the people who should hear the evidence first are the jurors. Then the public has a perfect right to hear the evidence, but not until the jury hears it. The media always want to give it all out before a trial because they want to be first, and that can have the effect of poisoning a jury-poisoning your chance to get a fair trial. I don’t have any issues with reporting a trial when it is going on. My issue is that the media don’t have a right to see evidence before the jury does, but the media disagree with me.

AT: Some media, not all media. There are a lot of really good journalists out there who respect your boundaries, right?

HH: No . . . Nobody respects your boundaries. Everybody wants to be first. There are a lot of good journalists out there, but they all believe that they have the right to get it before anybody else.

AT: I will respect your boundaries now and wrap this up. Is there anything else you want to mention, about anything at all?

HH: I have two basset hounds. One’s named Atticus and one’s named Scout and I have to go home and walk them and feed them now.

AT: Very appropriate. Thank you.

HH: You’re welcome.

AT: That was fun.