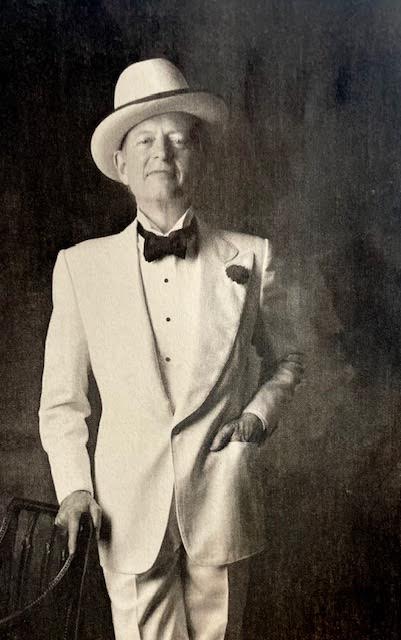

INTERVIEW WITH TOM WOLFE

When the U.S. National Parks Service breaks ground on the Mount Rushmore of Participatory Journalism, Hunter’s and Tom Wolfe’s profiles will be the first two they dynamite out.

These two fellow travelers re-chartered the map of literary journalism, beginning in the middle 1960’s with Wolfe’s The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine Flake Streamline Baby (1965) and Hunter’s Hells Angels (1967). Straddling the fiction/ fact line and writing consistently bold and flamboyant prose, together they reinvigorated the writing world as the Hemingway and Fitzgerald of the Age of Aquarius.

After a few years of correspondence, they met in the flesh for the first time in New York in 1969. Wolfe co-edited The New Journalism in 1973, a collection of works by the non-fiction writers of the day who were breaking the mold — Hunter, Wolfe, Norman Mailer and Truman Capote among them.

Since penning The Bonfire of the Vanities, the seminal 1980’s novel, Wolfe has written mostly fiction. President Bush has called Wolfe his favorite writer… but we won’t hold that agaisnt him.

He talked with The Woody Creeker editor, Anita Thompson, recently about his relationship with Hunter, his writing method and why American politics don’t deserve straight writing.

ANITA THOMPSON: Had you read Hunter’s work before?

TOM WOLFE: Yes, he had written some things, oddly enough, for this strange publication that the Dow Jones put out called the National Observer. And you can’t imagine a stranger match. He did some terrific things for them, and then came Hell’s Angels, and in that book I read that he had been at this party that Ken Kesey and the Pranksters gave for the Hell’s Angels, and I was not there. I haven’t even heard of them then, and so I remember giving him a call. I forget how I got his number, but I asked him about that event. Now this is something about Hunter that should be brought up: at least in my experience, Hunter was very kind. If you had something serious to talk about, he didn’t act like a maniac.

And he sent me tapes that were recorded at that particular party, which was a very generous thing to do, I thought. To me, just a gift at the post office is generous.

He was doing what I thought was the way to write. What he did was very much what I did. He really went to see things and, more than that, he joined in. And with the Hell’s Angels that’s not a small undertaking.

AT: Do you think Hunter’s work had any influence on your own?

TW: That’s entirely possible. I do remember when I was working on the New York Tribune, Jimmy Breslin’s work had an effect on me I remember specifically. I don’t remember specifically if Hunter’s did. I would read Hunter the way I read Henry Miller, which was when I was getting stale and the words were just coming up flat. I would read Henry Miller or Hunter and it was like putting carbonation in your brain.

And you felt like, “Hey, I’m back to life. I can actually write this thing.” That’s what I remember. By that time, I was probably too deep into my own mannerisms. I didn’t pick his up. Besides, he was inimitable.

AT: You called him the greatest comic writer of the 20th century in a Wall Street Journal Op-Ed.

Yet he was also part of a century-old tradition in American letters, the tradition of Mark Twain, Artemus Ward and Petroleum V. Nasby, comic writers who mined the human comedy of a new chapter in the history of the West, namely, the American story, and wrote in a form that was part journalism and part personal memoir admixed with powers of wild invention, and wilder rhetoric inspired by the bizarre exuberance of a young civilization. No one categorization covers this new form unless it is Hunter Thompson’s own word, gonzo. If so, in the 19th century Mark Twain was king of all gonzo-writers. In the 20th century it was Hunter Thompson, whom I would nominate as the century’s greatest comic writer in the English language.

– TOM WOLFE ON HUNTER S. THOMPSON WALLSTREET JOUNRAL FEBRUARY 22, 2OO5

TW: Yeah, and that’s not a small thing. I also compared him to Mark Twain, and for that matter, to people far less famous than Mark Twain, like Artemus Ward, Petroleum V. Nasby. These were things that people hadn’t seen before but, at the same time, let their fantasies run wild. It’s a very American thing. Twain’s first short story that brought him fame was one called “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County,” and it introduced readers to a life of miners in the West that most people had no idea about, but at the same time it was a fantastic story about this champion jumping frog who had been made to swallow BBs so he couldn’t jump very well. You knew that somehow there was a lot of embroidery, but you didn’t care. He did both things: introduce you to something real and new and, at the same time, a flight of fantasy. That’s what Mark Twain did over and over again. If you read some things like Innocents Abroad, Life on the Mississippi and those things, he’s constantly doing that.

AT: Do you have any guiding philosophies in your work, or a discipline that you follow in your writing?

TW: Everything I’ve done came out of journalism. Once I have the material, if we’re talking about a magazine or a book — I don’t consider essays real writing — then I will make myself do ten pages a day, triple-spaced, which is only about twelve or thirteen hundred words. If there’s time I’ll just quit right in the middle of a sentence and give myself the rest of the day off.

But it doesn’t do any good to just sit at a desk, because I can waste time at my desk superbly. When I did The Bonfire of the Vanities serially for Rolling Stone, I got interested in these people who really did that well. Not just [Charles] Dickens but [Emile] Zola, [Anthony] Trollop, and others. They all used a quota system.

AT: A quota system?

TW: Yes, because you quickly discover, as I’m sure Hunter did, that the things you produce when you don’t feel like writing are just as good as the things you produce when you think, “Yes, this is the day.”

AT: So it doesn’t always have to be fun.

TW: No. It was so seldom fun when I was doing it. It can be fun at the end of the day — when you say, ”Wow, people are going to love this,” but half the time you wake up the next morning and say, ”God, this is drivel.” Writing is a very artificial thing. You’re taking sounds and converting them to symbols on a page and you hope that the words will recreate not only the sounds but certain images in the mind of the readers. That’s tough going. It’s artificial. I think he was really just justifying taking drugs, but Kesey said, ”I’m tired of being a seismograph for measuring earthquakes. I want to be a lightning rod,” which he became, but it’s hard. I don’t really even trust people who say they’ve had fun.

I was always hot on newspapers. If you were absolutely blocked for leads or stories, start the sentence with the word ”with,” because it will force you to come up with something descriptive and specific. I’ve done that many times with newspapers.

AT: I guess in newspapers you would often be writing about politics, but you’re not a big fan of politics.

TW: No. I avoided getting stuck in politics. In fact, they thought I was insane at the Washington Post. I was sent down to Cuba to cover the Castro thing, and I wrote a long series about Cuba and Castro and all these things. I was down there about six months. I came back and the managing editor said, “How would you like to be our Latin American correspondent?” They didn’t have a Latin American correspondent and I said, “Well, it was a great opportunity, but I’d rather cover things like local news around Washington.” They thought I was insane, but you get into one of those beats and it’s like wearing blinders. You don’t see anything else and you don’t talk to any other kinds of people. Also, they want very straight writing when you re writing about politics. Politics doesn’t deserve straight writing.

AT: Why don’t you think it deserves straight writing?

TW: Because it’s as wacky as anything else that goes on. I did some daily stories from Cuba and the Caribbean, where arteries distended in anger. That always had cuts. But they were. You could see these damned arteries in their necks. They were so powerful.

AT: That’s what Hunter loved about it. The people were so volatile and crazy.

TW: It’s like once you start writing about banking. It’s not boring, because the people are crazy. Also, somewhere, I don’t know if I ever wrote it, but I said that the problem with writing about American politics as opposed to Cuban is that this is a very stable country — unbelievably stable. We don’t have parliamentary elections. The president can’t suddenly lose on a major issue and then have an election forced. And other people right now probably wish that we did have that system.

THIS COUNTRY’S GOVERNMENT IS LIKE A TRAIN. IT’S ON TRACK AND YOU CAN YELL AT IT ALL YOU WANT BUT YOU HAVEN’T GOT ANYWHERE ELSE TO GO.

When Nixon got forced out of office, Hunter did not rise up to take over on behalf of the Army. In fact, there were no demonstrations and I don’t even know of a single incident of some drunk Republican doin: something outrageous. Everyone watched on TV: “Oh look, Look at the way he’s making a V-for-victory sign as he gets on the helicopter.”

This country’s government is like a train. It’s on a track and you can yell at it all you want but you haven’t got anywhere else to go.

AT: Do you have any lessons or advice for young writers today?

TW: On the practical side, I think young writers should certainly exploit their own experience, but they should realize what Ralph Waldo Emerson said: “Every human being on Earth has a great autobiography to write if he can only figure out what is unique about his experience.”

But he never said everyone has to. So at some point you’ve really got to get used to reporting. There are no techniques for reporting. There’s only an attitude, which is that you have some information or you’re living a certain kind of life and I need that information, I need to watch you, and I deserve the information, I deserve watching you. And that’s the essence of reporting. It’s not that hard. It’s a kind of willpower — thrusting yourself upon people. And it’s amazing how many people around the world are actually delighted to have somebody ask them what they think and what they do. I’m talking about myself to you. It’s nice.

AT: I love it, too.

TW: And the other thing is, it’s very valuable to have a theory of life. The nice thing is it doesn’t have to be correct as long as it forces you to make connections. That was the thing about Marxism. I mean Marxism turned out to be a colossal fraud, but there are a lot of writers who do good things because being Marxist made them think about social classes and social classes made them think about the status of working people or middle-class people and all that. For that matter, religion is not very popular anymore, but that was the framework for people for, my god, centuries. And so I’m saying that anything will do.

AT: You need a starting point.

TW: Yeah. I believe in what I call “status theory” and it serves me well, but I could have probably believed in theosophy or Sigmund Freud and as long as I was systematic about it, it would have probably worked. And the other thing is advice that Sinclair Lewis gave in a marvelous essay called “How To Write”. The first sentence is, ”First, sit down.” Most writers spend most of their time dancing around the project saying to themselves, “I’m a writer. I’m going to write such and such,” but if you don’t sit down at some point it’s not writing; it’s not going to happen. Inertia is a huge factor.

Just getting yourself started, wherever you start during the day. It’s tough. But also, the more young people can read, the better. And I say that because if i had had television and internet when I was growing up, I don’t think i would have read a third as much as I did.

AT: Do you use a typewriter?

TW: By my preference, I would. But I was informed about six months ago that. I would have to start saving my ribbons to have them re-inked. I said that’s a sign that perhaps I should get into the 20th century. And so now I’m using a computer.

AT: Does it change your style knowing that you can move text around, or cut and paste?

TW: It’s wonderful for editing, but you know, when you get right down to it, it doesn’t really matter what you use in the actual writing. The most prolific writers were in the 19th century, and up to about 1920 or so they all used steel pens, and today you wouldn’t ever want to use a steel pen. You’d have to keep dipping the damn thing into the ink.

AT: It didn’t seem to slow them down.

TW: No, because you can’t really write that fast.