BY J. WINSLOW BASTIAN

Dear Woody Creeker

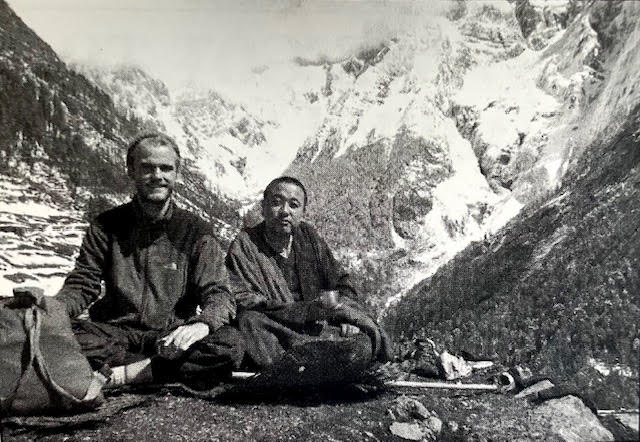

It has been an explosive year: 9 months in Asia living among Tibetan refugees and climbing Himalayan peaks, 2 months in Cali, Colombia sharing streets with devastating women guarded by cartel money, and now this — Woody Creek — a land with bountiful idiosyncrasies and history as bizarre as any hermitage in the world.

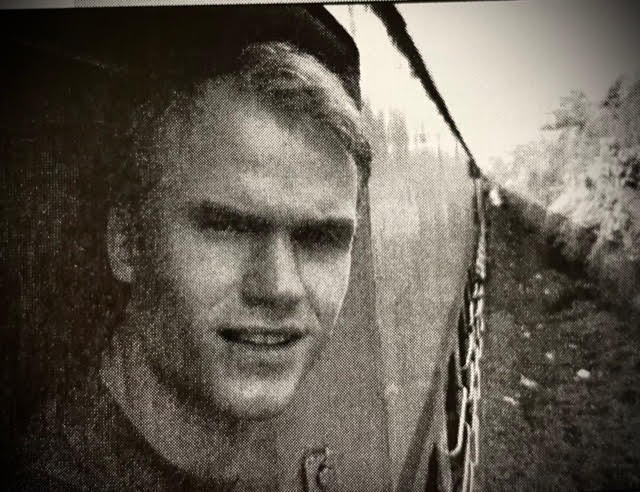

It’s been nearly ten years since I called the golden fields of Woody Creek Road home. And though my house is on the mesa no longer sits on the base of the Bastians, I have managed to move just a quarter-mile west to Owl Farm where I live as a 23-year-old sports writer for the Aspen Daily News with the esteemed managing editor of the sacrosanct publication, Mr Travers.

As my writing these days seems to lamely tote the line of an uninspired hack, I was hoping to share with you a few morsels from my travels to the Far East. The first of which — “An Ode to Woody Creek” — is a small letter I wrote home to Anita describing what it was like growing up in Woody Creek. The second is a journal entry from Bombay.

AN ODE TO WOODY CREEK

It is 2 a.m. on any given night and all of a sudden I jolt out of bed to hear a sound that is all too familiar to a Woody Creeker. You know what I am talking about: the subtle, refined, and elegant noise created only by the mixture of shot-gun rounds flying, screeching peacocks, and the whimpering cries of the coyotes up in the mountains. To most children, this apparent sound of hell would cause them to forcefully wake up and immediately piss their pants in sheer terror. But to a young lad raised in Woody Creek, these sounds represent more of a gentle lullaby or a classical symphony. Yes, perhaps we’ll call it the Woody Creek Symphony.

And if that image doesn’t ring any bells, then we’ll try another. It is now 7 a.m., and the sun has finally warmed Lenado, forked its way through the Flying Dog Ranch, and begun to heat the mesas of Woody Creek (side note: have you ever noticed how Woody Creek is like 100 degrees hotter than Lenado?). Anyway, I look out my window to see Jimmy running through the golden wheat fields, his body contrasting with the snow-covered peaks on all sides, and to welcome the morning he is playing a flute that my father brought back from Nepal years ago.

Look deeper into the valley, and you’ll see Hunter sitting behind his typewriter, the tavern opening its doors for another busy day, my mother meditating, the llamas grazing in the fields, and George driving down the road with a new batch of Stranahan’s Colorado Whiskey. With these sacred rituals flowing through the veins of each person privileged enough to have lived here, we begin another day in Woody Creek.

October 19, 2006.

When I found him he was completely sprawled out, clothes ad body worn sickly thin, but his eyes still open and staring straight to heaven; he was dead. I don’t know the reason, but fate dealt him an interesting spot to pass away: the stairs of the New Delhi train station. Interesting because he decided to put his rotting corpse on display to the thousands, maybe millions, of people who walk those steps every day.

Have you ever seen a dog die? Right before death they struggle with every last bit of energy in their withering hearts to die somewhere where they cannot be seen. Why? Maybe because they are embarrassed, or because they don’t want to give their killer the satisfaction of a public spectacle. Come on, you can relate to this. Remember when you were in college puking your brains out at some frat party? Did you want to puke in public or somewhere hidden from the cool kids? Same thing.

The people of India accept the greatest American fear: death. In a country of one billion people, where the overwhelming majority of them are desperately poor and have a life expectancy of 60 years or so, witnessing a dead man on the steps of the train station is just part of the daily scenery –something so expected and “mundane” that it is never even realized as ritual, like taking a morning piss.

A few days after the “dead-man-on-stairs” incident I traveled to Bombay by train, which I suggest to any person who is looking to greaten their knowledge of what it really means to be human on this unforgiving earth. I uphold this bold claim because just north of this twisted city rests the largest slum in all of Asia; this is a world fact. By train, you pass these slums for over one hour. Oh, sorry, and by slums I am referring to mile upon mile of nothing but shacks, tents, and blown-out cement structures, where every inch of land is used for the most basic elements of human life. Nothing I have ever seen, from Cairo to Mexico City, compares with this.

Also contained within this vast complex of chaos is the darker side of humanity: child slave markets, filthy prostitution rings, and black markets filled with anything your suppressed inner demon desires; think of a marriage between Tijuana and the devil, with a spattering of colonial architecture, and you are starting to get the picture of Bombay.

Later that night I was sitting in a chic, Bollywood-like high-rise apartment overlooking the city of Bombay. When enjoying a view of the ocean and a drink brought to me by one of the many servants, I looked down toward the street to see a hauntingly familiar image: more damn slums. And that is India: the millionaires living one block from the poorest people on earth, and every time the owners want to appreciate the ocean view from their plush little palace, they must first set their eyes upon mind-numbing poverty.

In comparison, what I love about the good old USA is how we just push all the poor people into small, confined areas and then pretend they don’t exist. We also do this with the elderly, the sick, and the disabled, shutting them off into their “homes” or “facilities” — our motto being: we will help you, but just get out of our sight, because your appearance actually makes us sick. Somehow the Indians never seemed to pick up on our ingenious solution for ridding our country of death, sickness, and physical ailments. Remember, we are Americans: if it looks OK, then it is OK.

And so what of our dead comrade on the stairs of the New Delhi train station? How do our fragile minds handle this? Somehow the memory will never leave my mind: like the steady current of a river naturally adjusting its course around a submerged rock, the people of India adjusted their course for the dead man, but kept flowing with the same intensity, never changing, never stopping.

Yours,

J. Winslow Bastian