BY WALTER ISAACSON

In addition to serving as President and CEO of The Aspen Institute, Walter Isaacson is a writer, biographer, thinker, force of nature and regular visitor to the kitchen at Owl Farm. Before coming to the Aspen Institute, Isaacson ran CNN and was Managing Editor of Time Magazine. He is the author, most recently, of Einstein: His Life and Universe.

It was fortunate for me that the good folks at the Aspen Institute dld not remember, when they were selecting me as president, my first visit to the campus, as a participant in one of Charlie Firestone’s media seminars in the late 1990s.

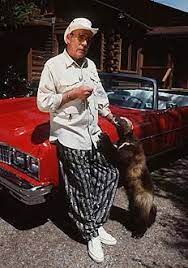

Hunter Thompson, whom I knew from various misadventures on campaign trails, gave me a call, asked what room I was staying in, and offered to come pick me up. A few minutes later, I saw his red shark convertible driving across the manicured lawn and marble garden of the Aspen Institute meadows .right up to the patio of my ground-floor room. A bellman from the front desk, who to my relief apparently retired soon thereafter, was waiving his arms and chasing the car.

Hunter took me off that night to the rock quarries, where he set up propane tanks that we shot with high-powered rifles. On the way, I struggled to find the seat belt, which he snarled that no one ever used. I decided I did not need to impress Hunter with feigned craziness or recklessness, and I put it on.

HE WOULD READ EVERY PARAGRAPH HE WROTE OUT LOUD, REPEATEDLY, SOMETIMES ACCOMPANYING IT WITH AIR DRUMS UNTIL ITS METER AND MELODIES AND BACK BEAT WERE PRECISELY RIGHT, LIKE A RIFF OF A JAZZ MASTER.

Yes, Hunter was crazy, but also crazy like a fox. The secret to Hunter’s writing, I discovered, and what makes him so important in the canon of American non-fiction, was that when it came to things that really mattered, like rhythm of a sentence or the use of a proper poke of punctuation, he was not as crazy or as reckless as he liked to let on. He would read every paragraph he wrote out loud, repeatedly, sometimes accompanying it with air drums, until its meter and melodies and back beat were precisely right, like the riff of a jazz master.

He came to my office at Time Magazine one evening to turn in personally a piece he had written, a punchy but melodious narrative tale about hanging around in Hollywood while Johnny Depp and others made a movie of “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.” Amongst the entourage he brought along to my office were Depp himself, whom he made read the piece aloud, and Lyle Lovett, who accompanied Hunter on air drums. Hunter swigged Chivas Regal, toked on a hash pipe, and awed the assemblage of junior writers and deputy art directors who gathered to see the show.

Hunter’s legacy to American writing was to unleash the excitement that could be brought to nonfiction by truly letting loose. But Gonzo journalism has another aspect that is not as properly appreciated. As practiced by Hunter, it was not only crazed but also crafted, very carefully crafted, sentence by sentence, paragraph by paragraph, fact by fact, down to every punctuation mark, with such a painstaking care that less practiced eyes could think it was spewed forth with all of the carefree abandon of a reckless ride across a marble garden.