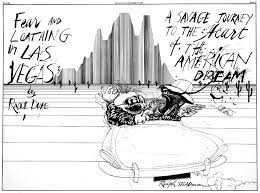

BY RALPH STEADMAN

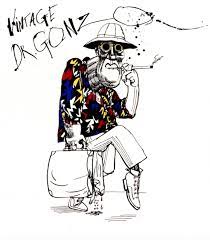

Social images are both aesthetic and cogent. They are magical shorthand marks, rumbustuous traveling street theatre, cheap and accessible for the best of possible reasons – to reach the people.

Much of the avalanche of engraved prints in England in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries was directed towards the lower echelons of London society. They were saucy, outrageous broadsides intended to titillate the less discerning or the downright filthy. But there was also a market for a sophisticated clientele who preferred their lascivious interests to be served with a degree of refined sleaze that only money could buy. These broadsheets contained political scandal and so much the better, for those portrayed were always higher up on the social ladder.

Allegorical scenes of vividly portrayed and recognizable personalities of the day in compromising positions were distributed surreptitiously among an elite with a penchant for explicit court scandal. These portable broadsheets were not intended to hang on tastefully decorated drawing room walls but to be nonchalantly slipped like gossip into the hands of those who enjoyed a joke at someone else’s expense — which is probably why they earned their reputation as examples of ‘low art’ — but nevertheless, although in the hands of masters like Hogarth, Rowlandson and Gillray, great levels of composition and displays of brilliant draughtsmanship were accomplished.

“WE ARE ALL PUT IN THE SAME MISERABLE POT, ALONG WITH THE HACKS AND THE GRUB STREET SCRIBBLERS — BUT AIN’T THAT THEY WAY WITH ALL CREATIVE ENDEAVORS, WHETHER COMMITTED ARTIST OR NEEDY HACK?“

The eloquence with which · these artists drew augmented the authority of their work. They persuaded the viewer that though these cartoons were allegorical fantasies, they could instruct a visually illiterate populace ravenous for a weapon that would drag the great and the good off their pedestals, reducing them to paper effigies to be torn into shreds. The cave painters were the original caricaturists, their victims, the animals they had to hunt to survive. The marks they made on tile walls of caves were not mere decoration, but an attempt to exorcise fear, to encapsulate within a line -the tangible identity of the next meal. The awareness of the aesthetic potential in these drawings was a slow process of enlightenment and sophistication, later to be exploited by all the great civilizations throughout history.

Leonardo da Vinci, for example, as evidenced in his drawings of grotesque faces, was fascinated by the difference between caricature and character and the degrees of wretchedness that could be achieved by persistent distortion. He realized that distortion loses its potency if it departs too dramatically from the authentic human bestial form to become merely a puerile exercise in linear dexterity.

Gianlorenzo Bernini, sculptor, painter and architect was the first, as far as I know, to simplify the art of caricature in the 17th century with his scribbled observations of cardinals, soldiers and French cavaliers. El Greco used the caricaturist’s art to elongate his figures for a practical purpose. For when viewed from below, the effect of optical foreshortening reestablished the natural proportions of the figures. It was not El Greco’s intention to show that we live in a world of ridiculously tall Apostles or anorexic Virgin Marys. Michelangelo, too, subtly used the caricaturist’s technique to adjust the viewer’s eye into a robust monumental physicality of his vision.

Hieronymous Bosch and Pieter Breughel, particularly, were able to characterize the hideous nature of our worst inclinations. They were the founders of an art form that graphically portrayed the constant transgressions in human behavior. Neither can Goya be ignored. His fantastical series of satirical etchings, ‘The Caprices,’ give us irrefutable evidence that the cartoonist has and always will thrive in the tradition of great art.

Hogarth, though his true ambition was to be a ‘serious painter,’ was the father of British satire. Under the tutelage of Sir James Thornhill, he became an artist as distinct from a craftsman. He discovered “a shorter way” to achieve the desired result through his need to catch the momentary actions and expressions of his subjects.

Gillray, too, learned his art through engraving, with a legitimate note bank printer called Harry Ashley. Etching became his ‘shorter way’ to achieve his urgent, contagious images with speech balloons: “To be read rather than savoured.”

This was the period when cartoonists discovered a new language, a short hand of devices and effects, which could match the speed of events. And thus from the political broadsheet came the birth of the newspaper.

This historian, Hazlitt, saw vulgarity in these works, which to him precluded the aesthetic. This damning view still dogs the satirist to this day. Caricature is, in Alexander Pope’s words: a “debased fad.” Thus we are all put in the same miserable pot, along with the hacks and the Grub Street scribblers — but ain’t that they way with all creative endeavor, whether committed artist or needy hack?

The cartoon became the people’s art — their weapon, debased for sure — but accessible. Something to hurl at those who would abuse their office and feed their own agenda. Not even a god has the right to mess with the rights of the people and politics should have absolutely nothing to do with God.