BY HUNTER S. THOMPSON

INTRODUCTION BY DOUGLAS BRINKLEY

One evening while editing The Proud Highway — Hunter’s first volume of selected letters — I stumbled across a cardboard box filled with frail, yellowish carbon sheets. I don’t remember the exact year, but Bill Clinton was president and Hunter was in a foul mood. We were on deadline to Simon and Schuster. Deadlines always made him edgy. Hunter kept his archive in his Owl Farm basement and I was down there all alone, poking around his aged correspondence for gems to include in The Proud Highway. That’s when I unearthed this trove of old papers from Hunter’s days in New York City circa 1959. Here were about a dozen unpublished short stories he

wrote after receiving an honorable discharge from the U.S. Air Force. The paper clips on the left-hand corners of all the stories had rusted, leaving deep indentations that spoke of decades past.

Gallantly, I headed upstairs to show Hunter the find. Certainly, I thought, these would cheer him up. Over the next few nights we read most of the stories out loud, with local friends like Oliver Treibeck, Gayle Golding, and Gerry Goldstein (among others) assuming center stage. He didn’t like most of the stories. He chalked them up as “juvenilia”. But “Fire In The Nuts”, a title used as a chapter head in The Curse of Lono, had him howling with glee. Originally titled “Hit Him Again, Jack,” Hunter redubbed it “Fire In The Nuts” in 2003.

He recalled typing the story while virtually broke in New York wandering around Manhattan by day and pounding beers at night. Literature, however, was always on his mind. He was determined to become a great American novelist, albeit one with a “White News” dissident bent, like Norman Mailer. If Sherwood Anderson could write about “grotesques” in Winesburg, Ohio, Hunter was going to profile “rogues” in New York. When I asked him who exactly the characters in “Fire in the Nuts” were modeled after, he chuckled and launched into a mock raid response. “Ratty people, Dougie,” he said. “That’s all you need to know.”

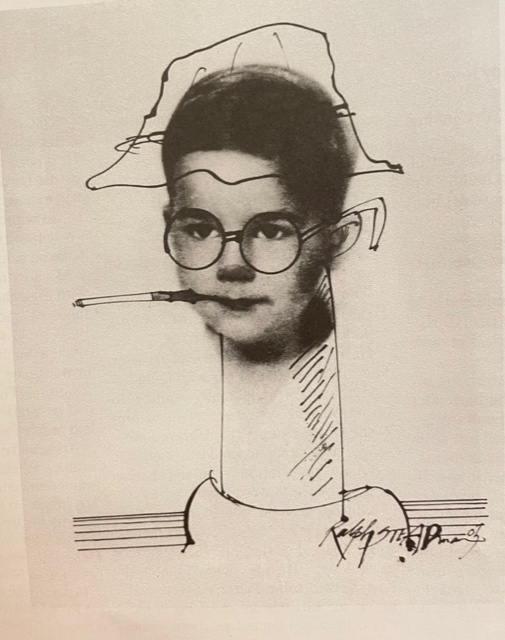

Harrison Fieler was vastly talented. Of this, he was certain — for it had been pointed out to him all his life by old women at his large, Midwestern high school, by old men at his small Eastern college, by young men in the army, and finally by young girls in Greenwich Village — where he came, in the flush of his vibrant youth, to live, work, and climb the ladder to fame and

immortality.

But for all his raging talent, Harrison Fieler was painfully unsuccessful. In five years, he had gotten nowhere.

After three semesters, he gave up on the Art Students’ League and joined Actors’ Equity. While working as a stagehand at an off-Broadway theatre,

he wrote a play. It took him two years, and the play was a dismal failure. No

one would even read it through. His best friends, after listening to the first act, advised him to try another medium.

So he looked for a job, and found one in the mailroom of a large advertising

agency. Here, he made progress. Soon he was a junior copywriter, whipping

off jingles, pounding out slogans, and participating quite vigorously in the

economy. He bought several new suits, paid the rent on time, and ignored the sneering comments of his old friends.

BUT FOR ALL HIS RAGING TALENT, HARRISON FIELER WAS PAINFULLY UNSUCCESSFUL. IN FIVE YEARS, HE HAD GOTTEN NOWHERE.

But, as the pressure mounted and the good times rolled, he found he was developing manic-depressive tendencies. One moment, he was quipping and joking with the boys, and the next, he was floundering in a bog of fear, insecurity and mounting frustration.

For a period of several months he was impotent, and thought of killing himself. His inadequacy was so obvious that he was fired from his job. The boss was kind: “We don’t know exactly what’s wrong with you, Fieler, but we feel you’re losing your grip. Why don’t you rest for a while, then try a different field?”

So Harrison Fieler went on unemployment insurance and worked on a novel. Miraculously, his potency returned: slowly and doubtfully at first, then with a rush — until, after two months on unemployment insurance,

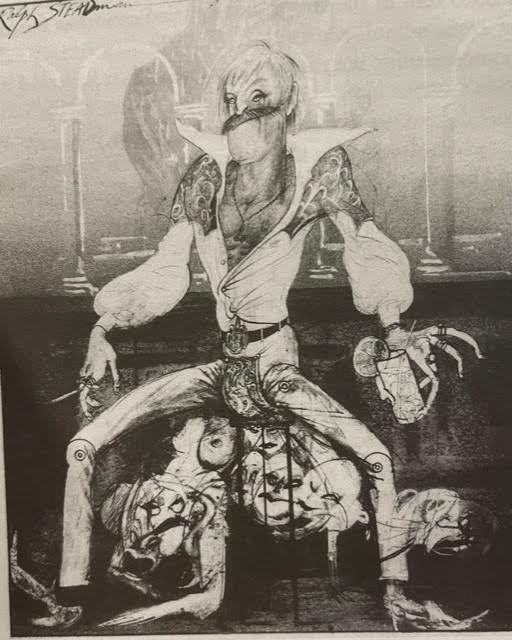

he was a throbbing, sexual beast. He prowled the Village streets, chuckling

happily and wondering if people could see the satyr in him. He stroked choice thighs on rush-hour busses, and was often embarrassed on crowded subways when the fire in his groin became an awkward, visible reality.

His satyr period, full and fiery though it was proved short and exhausting. He soon tired of the girl’s he’d been dealing with, and began to cast about desperately for something new. The dread spectre of impotence stalked him in the streets and he tried countless forms of erotic stimulus to fend it off. He even considered homosexuality. but dismissed the idea when he found it didn’t excite him. He feared the censure of his old friends, and besides, queers were disgusting.

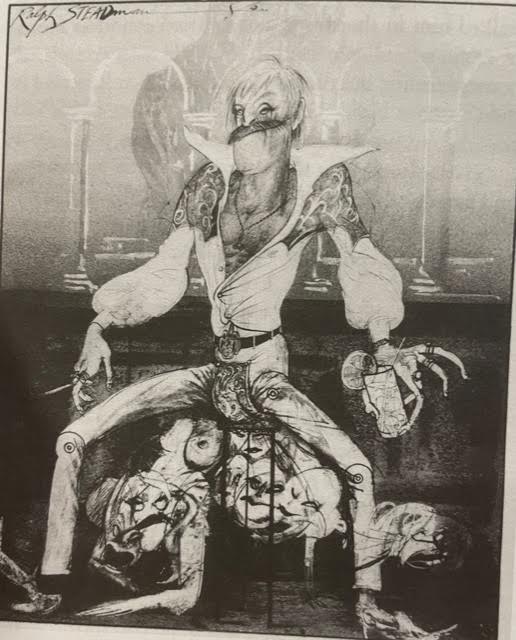

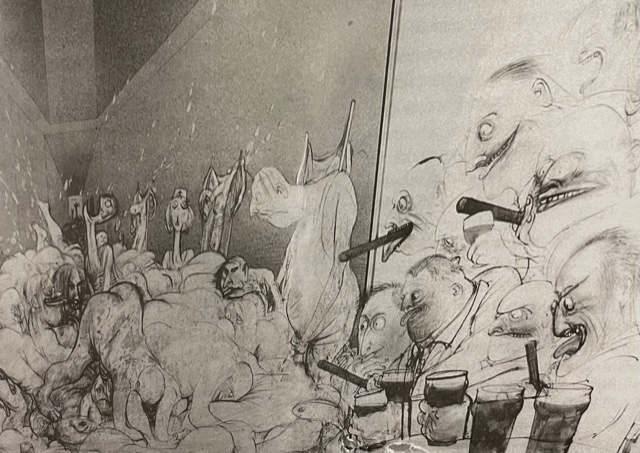

He took refuge in sleep, often staying in bed twelve and fourteen hours at a stretch, and hardly eating at all. The pressure of boredom usually drove him into the street by later afternoon. He became a sexual shark, roving from one Village bar to another, in search of bored or lonely women. He made friends with other sharks, and often they roamed together, looking as sharks will for floating garbage or struggling, helpless bodies. They preyed, singly and in packs, on all those too weary or crippled to fight back: the lonely, the desperate, the trusting, and always the weak.

Harrison Fieler — he of the raging talent, and the great promise of the once-vibrant youth — came to hate his own image in the mirror. Goaded on by the pain in his rotting core, he worked the bars in search of prey, in search of hope, in search of kicks to bring him back to life.

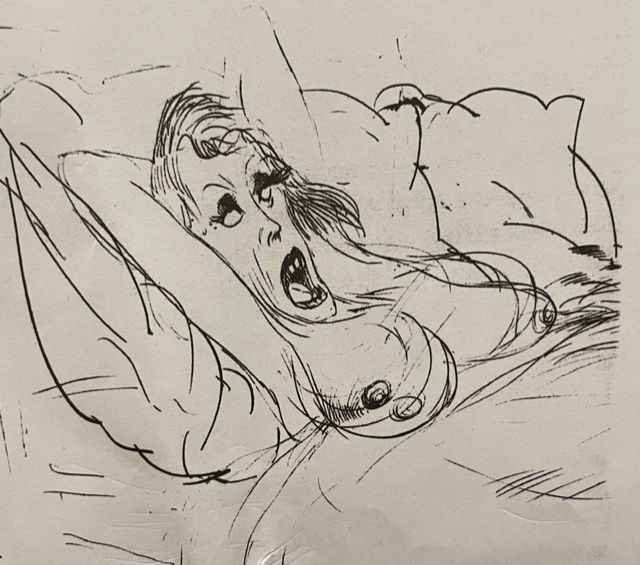

One Sunday morning in November, he awoke with a strange itch in his soul,

a feeling he hadn’t had in months. The night before had been so awful that he hated to think of it. He had met a girl, and known instantly that she was The One. She was very young, with a face so innocent that he found it beautiful. He found her at a small party on Sullivan Street, and told her at once of his threatening impotence. They walked the streets for several hours while he told her of his painful existence and begged her to come home with him. She cried, and he cried with her. Finally, when he threatened to kill himself if she turned him down, she relented. He promised, swore, and crossed his heart that she would be his salvation; she and she alone could bring back his precious manhood. They kissed passionately in a doorway on Bleeker Street, and she cried softly as he led her through the cold streets to his tiny apartment.

This time, failure drove him berserk. He beat her with his fists, calling her a dirty whore while she screamed in terror and thrashed about on the bed beneath his trembling body. She pleaded, offering to do anything he wanted, and he beat her again for taunting him.

Finally, he collapsed on the floor, sobbing hysterically, while she locked

herself in the bathroom, dressed, then fled down the stairs to the early morning street. Sometime before dawn he crawled to the bed and passed out, wanting more than anything else to die, to some how escape this misery and disgrace, to simply lie down and quit, refusing to play a game that hurt and he tricked him each time he made an effort.

But now, as if that cascade of horror had cleansed his failing soul, he awoke with an odd feeling of excitement, a sense of imminent progress and, perhaps, even salvation. He got up and looked at himself in the mirror. He was still young, not even thirty; his thick brown hair had begun to recede, but with his crew-cut, you could barely tell it. A few exercises would knock off that pot-belly and put some flesh on those bony shoulders; he would have to begin eating, getting to bed on time, and cut down considerably on the drinking.

THEY PREYED, SINGLY AND IN PACKS, ON ALL THOSE TOO WEARY OR TOO CRIPPLED TO FIGHT BACK: THE LONELY, THE DESPERATE, THE TRUSTING, AND ALWAYS THE WEAK.

The thought of food sent him to the refrigerator but, except for two cans of beer and a withered lemon, it was empty. He found his pants on the other side of the room, and counted his money: six dollars and seventy-eight cents until Tuesday, when the would come. To hell with it: if he ran out, he could borrow. A man had to have food, especially if he was trying to get a grip on himself.

He pulled a pair of old khaki pants , a dirty blue button-down shirt, and a tweed jacket he’d had since college. Not so bad, he thought, eyeing himself in the mirror. Tomorrow I’ll take everything to the laundry.

The half-block to the delicatessen seemed like a mile. He leaned into the wind, cursing as it stung his face and swept through the thin wool of his coat. Still cursing, he slammed the door of the deli behind him and quickly lit a cigarette. The smell of food made him hungrier than ever, and he bought a grapefruit, a pack of sweet-rolls, and some coffee. On the way back to the apartment, he bought a Sunday Times, the first newspaper be had read in weeks.

He toasted the rolls in the oven, made coffee, and cut the grapefruit with a dull knife. Then he knocked a heap of dirty clothes off the card table, moved it over to the win-dow, and set a place for himself, facing the street. When the coffee was ready, he brought the pot over to the table, got the front page of the Times, and sat down to a leisurely breakfast.

After reading most of the paper, he wondered what time it was. His watch was in the pawnshop and his phone had been taken out over a month ago. His curiosity gradually became an obsession, and he considered going down the hall to the next apartment and asking someone. Then he remembered; by getting out on the fire escape, he could see a clock in the window of a laundry across the street. He climbed out, shivering in the blast of cold wind, and saw that it was three-fifteen.

Now, back in the apartment, what to do? Andre’s didn’t open for another hour and fifteen minutes, but he didn’t feel like wasting his afternoon in a bar, anyway. The feeling of excitement was still with him, and he wandered around the room, finally pausing to stare out the window. An old melon rind lay squashed in the street below, and the wind blew tiny flakes of soot, like a flurry of black snow, along the fire escape outside his window.

Yes, by Jesus, he’d work on the novel. He hadn’t touched it in three or four months, and if he was ever going to finish it, now was the time. When the unemployment ran out, he’d have to go back to work,

But the novel bored him. He’d only written a chapter and a half, and even when he was writing, he suspected it wasn’t any good. Now he was sure of it. The only thing to do was start something fresh; not another novel, but something short and quick — a story.

He found his notebook under the bed; the novel took up most of it, but there were a few empty pages near the back. Then he sharpened a pencil with a kitchen knife and sat down at the table, wondering all the while what he could write.

The apartment was hot; he stood up to take off his shirt and pants. Then, before getting to work, he went over to the refrigerator and opened a beer. Now he was ready.

He felt intensely literary, sitting there in his underwear, all alone in the middle of Greenwich Village. How many others had trod the same path? Wolfe? O’Neill? Who else? Well, there was Bodenheim. Jesus, anything but that.

He forced Bodenheim out of his mind, trying to concentrate on a plot, even a subject. The army? He’d always wanted to write a story about the army, really blast the bastards. Maybe satire; he had a flair for satire. Yeah, that was it — pit an oddball against the system, and rip the army to bits. Now he could see himself in Andre’s. Casually mentioning the story he’d just finished. They probably wouldn’t believe him — he never paid any attention to those bums who were al-ways talking about the great novels they were writing, the fabulous paintings they had in the works — but when he came in flashing the check, huge and beautiful from one of the slick magazines, they’d fall all over him. He could see it now: discussions of his work in the quarterlies, himself back home on vacation, parties in his honor, soft lips spilling secrets into his ear — he’d have it made.

The page was still blank, and he forced himself to concentrate. Just pitch right in and let the story work itself out.

He jotted down a sentence: “The latrine echoed with laughter and conversation that night, but Ivan Ace was having none of it.” He paused. Why was Ivan Ace having none of it? “Ivan Ace was angry. He had just been put on KP.”

Why was Ivan Ace put on KP? He stared out the window, sipping his beer.

What heinous offense did Ivan Ace commit? He doodled on the paper, drawing a large box, carefully separating it into forty squares. Had Ivan Ace been drunk? Had he stolen? Did he get into a fight?

Time passed, and he constructed another forty-square box. What time was it? He climbed out on the fire escape and looked at the clock. Ten of four. Forty minutes until Andre’s opened. He went to the refrigerator and opened another beer.

Back at the table, he stared down at the paper in disgust. It was worthless, and he ripped the page from the notebook.

Now he started again: “Ivan Ace was a worthless soldier. He drank, stole, cheated, and pissed in potato barrels on KP.” That was more like it, by god. No beating around the bush.

THE PAGE WAS STILL BLANK, AND HE FORCED HIMSELF TO CONCENTRATE. JUST PITCH RIGHT IN AND LET THE STORY WORK ITSELF OUT. HE JOTTED DOWN A SENTENCE: THE LATRINE ECHOED WITH LAUGHTER AND CONVERSATION THAT NIGHT, BUT IVAN ACE WAS HAVING NONE OF IT.

What now? What made Ivan Ace tick? Was he impotent? No, that would be hitting too close to home. Besides, why would an impotent man piss in potato barrels?

More time passed, but no story came to Harrison Fieler’s mind. He finished his second beer, and climbed once more to the fire escape. Four-twenty. Andre’s was almost ready to open.

Maybe he should go on over, have a few beers, and come back later to work on the story. He would be more relaxed then. He always loosened up when he drank — two beers hadn’t quite done the trick. The more he thought about it, the better it seemed. This writing was a real bitch, and once you laid off for a while, you had to ease back into it. He had a good beginning; now he needed a few beers and a little time to think.

Andre’s was a few blocks across the park, and as he approached, he saw Duke Knaxon coming from the opposite direction. Knaxon smiled broadly and waved; when they’d reached the front door, he quipped his familiar greeting: “Buenos dias, old man –how’s it hanging?”

Fieler winced. This particular remark was almost more than he could take. He half suspected that Knaxon knew of his malady — possibly through the grapevine –and he was always careful of his reaction, for fear of giving himself away and confirming any suspicion the other was harboring.

Even the Spanish salutation annoyed him. Knaxon claimed he picked it up in Cuba, where he went down to fight with Castro — but Fieler knew better. Knaxon had started for Cuba, all right, but got no further than the Spanish section of Tampa, where he was arrested for possession of marijuana.

“Any action last night?” Knaxon asked as they seat-ed themselves at the deserted bar. They were the first customers of the day.

“A little,” Fieler replied. “Nothing special.”

Knaxon smiled. “Jack said you took off from that party with a real prize.”

Fieler felt his scalp go tight with fear. The shame and terror of the night came on him with a rush. Had she told any-one? Jesus, that would finish him! He felt Knaxon watching him, waiting for a reply. He forced a sickly smile: “Yeah. She was okay.”

“She swung?” Knaxon asked.

Fieler nodded, but felt the need to reinforce his story. “Yeah,” he repeated, “I just sent her home a little while ago. She was wearing me out.”

Knaxon chuckled. “You do all right, old man. I got rid of mine as soon as I woke up. Man, she was nowhere –kept wanting to get me in these degrading positions. Not bad at first, but it got pretty hairy after a while.” He chuck-led again, then became serious. “Yeah, after I ran her out this morning, I sat down and wrote some damn fine poetry –really got my soul into it.”

Fieler nodded. “Oh yeah? That’s funny. I’ve been working on a story most of the afternoon. I just came over for a few beers, then I’ll head back and finish it.”

“We’ll make it one of these days,” said Knaxon. “Just give me a break, that’s all I ask.”

“Right,” said Fieler. “But you’ve gotta make your own breaks in this racket. We didn’t pick the easiest way in the world to make a living.”

Knaxon stared soulfully into his beer. “But there’s nothing like it, when you get that vision,” he said quietly. “Nothing like it in the world.”

“I know what you mean,” said Fieler. “I got so excited today that I nearly went crazy. It just poured out of me.”

Several more people came in, and they moved to a booth in the rear. Har-vey Small, just returned from eighteen months in a California reformatory, bought a round of drinks. No one seemed to know the exact nature of his crime, but Knaxon said he had stolen at least a hundred cars. Nor did anyone know where his money came from. But he was a good fellow, always ready to buy a round, and was said to be a very talented actor. Fieler suspected he was also a bit queer, and was always a little nervous sitting next to him.

Across the table with Knaxon was a tall, collegiate looking fellow named Ted Wellman. He was an artist. During the day, he worked as a media-buyer for one of the ad agencies; at night, he painted.

They drank for several hours, and suddenly, when Harvey Small suggested they have some food, Fieler discovered he’d run out of money. Jesus, he thought. Five dollars shot to hell. He decided to wait until Knaxon was a little drunker, then hit him up for a loan.

Just about that time, Knaxon announced that he had to go uptown for dinner. “Some girl from home,” he expplained. “A friend of the family — I can’t dodge it, or the man might cut me off.”

The phrase “some girl fom home struck a receptive chord in Fieler’s brain. He knew that Knaxon was an:d thing but the starving poet he seem to be. He was Duke Charleton Knaxon the Third, of the Lake Forest, meat packing Knaxons, and any friend of his family’s was bound to have a whomping trust fund floating around some where in her background. If she was at all decent — even passable — he, Harrison Fieler, would lay hands on her with out delay. The only problem was to get Knaxon to bring her down to Andre’s after dinner.

“Say, Duke,” he said quickly. “We may have a little brawl up at my place later on. If this girl is anything but a sure loser, why don’t you bring her on down after dinner?”

“Good idea,” Knaxon replied. “But I’ll have to see what she’s like first. I used to know her a long time ago, but she might have changed.”

Then he was gone, and the three of them sat back for several more hours of drinking. Fieler persuaded the bar-tender to put him on a tab until Knaxon returned. “He owes me some money,” Fieler explained. ”I’ll pay when he comes back.” Then he ordered a steak sandwich from the kitchen

By nine, he was back at the bar, talk-ing to a short blond girl who was sit-ting alone. She was a little too old, a little too heavy, and a little too loud –but Fieler couldn’t have cared less. He was waiting for Knaxon to bring in the big game.

The girl eyed him. “I hear they keep studs around here,” she said with a grin. “Are you one of them?”

He blinked. “Studs?”

She laughed, slapping the bar with a pudgy hand. “That’s right!” she shouted. “I’m waiting for the STUUDDS!” Her voice blasted through the smoke, and several pairs of eyes swung quickly in her direction.

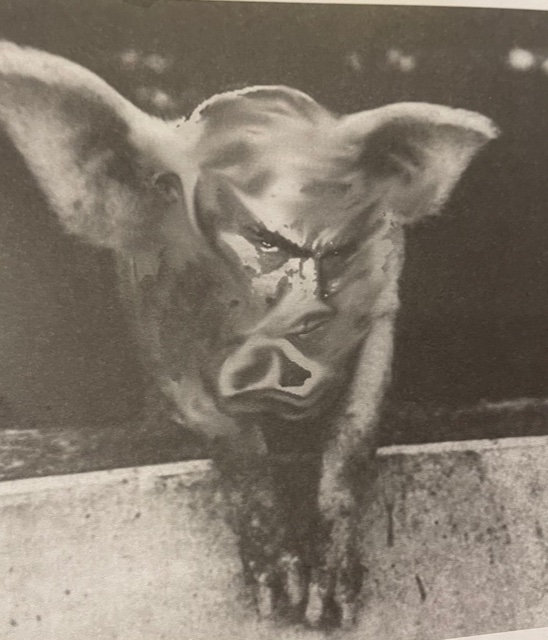

Fieler stared at her, his mmd functioning slowly in a fog of beer. Dumpy old whore, he thought. Drunk as a dog, yelling about studs — what the hell is the world coming to?

She swayed toward him, “I know,” she said. “I know what you’re after. Men don’t fool me.”

“That’s right,” Fieler agreed. “You know.”

She giggled. “Men like me,” she said with a coy smile. “They know they can’t fool me.”

Fieler put his hand on her thigh. “I could tell that,” he said earnestly, ”I knew it the minute I saw you.”

She smiled. “I like you. What’s your name?”

“DeSade,” he said with a grin. “Marvin DeSade. Just call me Marvin.”

She giggled. “Remember, Marvin, you don’t fool me.” Then she reached for her mug of beer and drank it off. “Say,” she said with a chuckle, “did I tell you about the guy who got his balls cut off in the Astor Bar?”

He winced, and shook his head.

“Later,” she whispered. “I think we understand each other.”

He looked at her, and suddenly it came to him that she was It. Here was the breakthrough he’d been waiting for. She was so repulsive, so cheap and foul so perfect in her way, that it sent erotic tremors racing up and down his spine. A vision flashed through his mind: the two of them together in his apartment — her, naked and fleshy, hunched in a corner with her back to the wall, him-self standing above her, screaming hysterically as he thrashed her body with a thick rope; both bodies covered with sweat, writhing and jerking with desire, while their scream mingled in a frenzy of perverted joy.

The idea excited him tremendously. He felt himself quite capable of such a thing. Nothing wrong with a spurt of sadism now and then — perfectly normal in these troubled times. He chuckled. And after it’s all over, he thought, I’ll buy her a grapefruit.

He laughed aloud now, swilling down his beer and thumping the empty mug on the bar. The girl, who had been staring sadly down at the floor, looked up at him and smiled helplessly. “What are you thinking, Marvin?”

He chuckled again, and squeezed her thigh –gently at first, then viciously, as the thick flesh gave way beneath his fingers.

She jumped, yelping with pain, and pried his fingers from her leg. “You’re cruel!” she exclaimed. “I bet I’ll have a nasty bruise from that!”

“That’s nothing,” he said with a lewd smile. Wait until we get to my apartment.”

“Hah!” she snorted. “Not on your life!”

“You’ll go,” he said. “I’ll carry you if I have to.”

“Just try it,” she said. “I can ruin you with one blow.”

Jesus, he thought. She’s just the type to do it, too. He glanced down at her plump body, wonder-ing if she was worth the effort. His vision returned, and he knew he had to have her. His potency, his very manhood, depended on it.

The bar was filling up; Fieler drew his last sober breath somewhere around midnight. The writing would have to wait his only thought now was to somehow lure this wretched woman to his apartment. She finished her beer, and he leaned toward her: “Ready to go?”

“Where?”

“To my place,” he said. “I’ve invited some people up for an orgy.”

She hesitated. “How ’bout one more beer?”

He wondered if the bartender would let him put two more on the tab. Christ, if Knaxon doesn’t come back, I’m done for.

She didn’t wait for an answer, but ordered the beers herself. The bartender eyed him strangely, but said nothing.

She squeezed his elbow, and just as he was about to lift his mug to his mouth, he saw Knaxon come in the door with one of the finest looking girls he’d ever seen in his life. The sight of her made him tremble with excitement. He saw Knaxon lead her to an empty booth on the other side of the room, then turn around and head for the bar. “Duke'” he called “Come on over. Where’ve you been?”

Knaxon approached, obviously far under the weather. “Hell,” he muttered. “She’s drunk me under the table.” Then he grinned: “I’m ready for the orgy, old man. Where is it?”

Fieler looked over at the booth. “Pretty soon,” he replied. “You sitting over there?”

Knaxon nodded. “Yeah, come on over. I’ll get some more drinks.”

They were halfway to the booth when Fieler felt the hand on his arm. “Wait a minute,” she said. “Wait for me.”

He turned around, but kept moving. She followed, and halted with them beside the booth, apparently waiting to be introduced. Now she revolted him — she was no longer the depraved messenger of his long-awaited salvation, but a dumpy camp-follower, fat and shabby as a Jersey City tavern whore.

Knaxon seemed not to notice her. “Harrison Fieler,” he said, “Mina Patterson.” The girl smiled, and Fieler started to sit down. Then he noticed that both Knaxon and Mina Patterson were staring at the girl beside him. For a moment, he was tempted to shout something like, “Be off, strumpet!” and send her on her way.

Just then, without waiting for an invitation or even an introduction, she sat down. All three of them watched her curiously; Fieler decided to take the bull by the horns. “This is my woman,” he said proudly, winking at Knaxon. “My woman, Pugo.”

Her head snapped around. “Pugo?” she exclaimed. “What the hell do you mean, Pugo? My name’s Connie!” She smiled with great dignity at Knaxon and his date. They introduced themselves.

Fieler took the drinks from the waiter, then pulled out a cigarette. “Got a match, Pugo?” he asked.

“Shut up with that Pugo business!” she snapped, rooting in her purse for a match.

Knaxon offered his lighter, and Fieler drew the smoke deep into his lungs. He’d been watching Mina Patterson out of the comer of his eye, and knew he had to have her. But what the hell could he do with this shoddy pig at his side? To hell with her, he decided. Maybe Knaxon can deal with her.

Mina Patterson was small and blond with high cheekbones and large, brooding eyes. Sensuous, he thought happily. Christ, sensuality and money, too. What a combination! For the first time in weeks, he felt a pre-coital stirring in his groin. The sensation so excited him that he quaffed his beer in a single gulp and ordered another round.

At the end of an hour, he was steaming drunk. When Mina Patterson said she wanted to come to New York and study art, he got so excited that he spilled his beer on his lap.

“But I’ll have to work,” she said, “and Duke tells me it’s hard for an artist to get a job in New York.”

Fieler’s woman, who had said nothing for several minutes, suddenly leaned forward. “That’s right,” she said bitterly. “No artist can get a job in New York. I’ve been on unemployment insurance for five months.”

“Come on now, Pugo,” said Fieler. “Don’t try to tell us you’re an artist. I really don’t think I could stand it.”

“What do you mean?” she snapped. “I’m as good as anybody. People admire my drawings — qualified people.”

Fieler hung his head. “Oh Jesus,” he muttered. “The shame of it.”

Knaxon was grinning. “I’ll tell you what, Pugo,” he said, “Maybe we — “

She slammed her fist on the table. “My name is Connie!” she hissed. “The next time anybody calls me Pugo, I’ll leave!”

Fieler, swaying drunkenly in the booth, was ready to lean over and whisper “Pugo” in her ear, but Knaxon was already talking. “Pardon me. Say, Connie, how would you like to make a little money?”

Her eyes narrowed. “What are you getting at?” she growled.

“I want you to help me sell something,” he explained. “There is a hell of a lot of money in it.”

“Why me?” she demanded. “Why not him?” She pointed at Fieler.

“Well, you’re an artist,” said Knaxon. “That makes a difference.”

She eyed him suspiciously.

“Now don’t get edgy,” he told her. “I sell a very rare type of oil. It goes for fifty dollars a quart.”

Don’t kid me,” she warned. “What do you take me for, anyway?”

Fieler smiled meaning-fully at Mina Patterson. Earlier, he had tried to touch her leg beneath the table, but she had moved out of his reach. Now he reached across and took her hand. “When are you coming to New York?” he asked, staring into her eyes.

Without looking at him, she drew her hand away. Knaxon was still talking, and she seemed to be interested.

“What kind of oil is this?” the plump one demanded. “What kind of oil sells for fifty dollars a quart?”

Knaxon leaned forward, looking around to see if anyone was listening. “It’s peyote oil,” he whispered. “For the armpits.”

Fieler burst out laughing, and the plump one sneered loudly.

“Huh!” she said. “You think I’d fall for a thing like that?”

“I’m serious,” said Knaxon. “You can make a hundred dollars a day selling it.”

“What is this stuff?” she snapped. “Nobody puts oil in their armpits.”

“That’s just it,” he exclaimed. “It’s foolproof.”

“You mean it does something to you?” she asked.

“Oh, the kicks!” Knaxon exclaimed. “It drives you right out of your mind!”

Her expression changed. For a moment it had been faintly, almost reluctantly, interested. Now she was stammering with indignant rage.

“It’s dope!” she shouted. “You want to get me peddling dope.”

Knaxon grinned, “Not dope, just oil.”

“Why, by god! You ought to be locked up!” she yelled. “You’re one of these lousy degenerates that ruins people’s lives!” There was a note of hysteria in her voice. “You want me to sell armpit oil! Crazy oil! Get me put in prison!”

At this, something snapped in Fieler’s mind. He swung around in his seat , suddenly wild with anger. “Shut up, you pig!” he shouted. “God damn your fat mouth, anyway!”

She turned on him, her mouth working rapidbly, but making no sound. Then she erupted again. “You crazy son of a bitch!” she screamed. “You dirty, lousy, drunken bastard!”

A silence fell on the bar, and a row of heads turned to see what was happening.

Fieler’s temper was out of control. With a quick shove, he sent her sliding into the aisle, where she thumped onto the floor like a huge medicine ball. “Get out o here, you loud-mouthed frump!” he shouted. “Just get the hell away!”

She sat on the floor for a moment, looking dazed and silly. Then she scrambled to her feet, jerked her half-full mug of beer off the table, and dashed it in Fieler’s face. Almost simultaneously, she picked up another mug and threw it on Knaxon. Mina Patterson, caught in the cross-fire, tried vainly to protect her fur coat.

The frump, still cursing like a trooper, ran toward the door as Fieler jumped to his feet. “You sleazy bitch!” he shouted, and, without think

ing, picked up the mug and hurled it at her back. It missed, and smashed against the woodwork beside the door.

An ominous silence fell over the room; suddenly the bartender appeared at Fieler’s side, grasping his elbow. “What the hell are you trying to do?” he snarled. “You could have killed somebody with that!”

Fieler jerked away from the bartender. “Wait a minute!” he said desperately. “Wait a minute. I want to talk to Mina. It’s important.”

BY NINE, HE WAS BACK AT THE BAR, TALKING TO A SHORT BLOND GIRL WHO WAS SITTING ALONE. SHE WAS A LITTLE TOO OLD, A LITTLE TOO HEAVY, AND A LITTLE TOO LOUD — BUT FIELER COULDN’T HAVE CARED LESS.

She hesitated, then took a step toward him. Both Knaxon and the bartender watched suspiciously as Fieler drew her toward the hallway to the kitchen.

“You’ve got to come home with me!” he whispered. “I need you!”

A look of terror came into her face, and she pulled away.

“I’ll explain!” he said, grabbing her shoulder. “You don’t know how important it is! You’re the only person who can help me!”

She was about to speak when Knaxon appeared at her side. “What the hell are you trying to pull, Fieler?” he shouted. “You sneaky bastard! I know your tricks! I know what you did to that girl last night!” He propelled Mina Patterson toward the front door, and Fieler heard it slam as they went out.

His brain seemed numb. If Knaxon knew, they all knew. He leaned against the wall, suddenly feeling sick and weak. Then he noticed the bartender staring at him.

“Don’t worry,” Fieler told him. “I won’t cause any more trouble. I’m go-ing.” Steadying himself on the booths he started for the door.

“Just a minute, ace,” said the bar-tender. “What about this tab?”

Fieler tried to think. The tab. Jesus, he was supposed to borrow some money from Knaxon.

“A little matter of sixteen dollars and twenty cents,” the bartender snapped, reaching out and grabbing Fieler’s shoulder. “Plus fifty cents for the mug you broke. That’s sixteen-seventy.”

Fieler slumped agaisnt the booth.

“I’ll pay it,” he whispered, conscious that everyone at the bar was watching him. He closed bis eyes and held onto the booth. “Just let me go. I’ll pay it tomorrow.”

“The shit you will!” the bartender shouted, jerking him away from the booth. “I’m tired of giving you drinks, you rotten bum! If I ever see you again, I’ll beat your ass till your nose bleeds.”

“Please,” Fieler whimpered, “I’ll get the money. Let me go, I’m sick.”

The bartender jerked him toward the door. “It’ll be worth that much not to have you around,” he snarled. “Now get out!” He opened the door and shoved Fieler into the street.

Somewhere in the distance a subway rumbled past, and above the city the proud shaft of the Empire State Build-ing swung its great beams of light across the sky. A bitter wind blew in from the Hudson River; Harrison Fieler pulled his collar up around his ears as he hurried through the empty streets to his apartment.

He passed a newsstand at Sheridan Square, but had no desire for a paper. He bad three cigarettes left, and lit one of them as be started across the park.

The trees were bare now, and the great arch was dark and lonely in the early hours of the morning. Leaves covered the sidewalks and the sounds, as he shuffled through them made him think of his yard at home.

His parents had paid him a dollar to rake the yard, and he would get all the leaves into a big pile in the drive-way, then burn them. He tried to remember the smell now but his memory failed him. For an instant, he wanted to get all the leaves in the park in a huge pile beneath the arch and set them on fire. New York needed something like that — a great leaf-burning in Washington Square. And he, Harrison Fieler — persona non grata at Andre’s writer of no talent, beater of women, possessor of no money, and natural-born loser — would be the master of ceremonies.

He remembered the Square back m June: trees blooming, folk singers around the wading pool. It had been good then; and summer, with the free concerts on Wednesday nights, had been that much better. He wanted to lie down in the grass again with a girl and a quart of beer and listen to some Bach.

He waded through a pile of leaves kicking them all over the sidewalk, and wondered why summer seemed so long ago. Time now seemed so short, so wasted; what bad he done? And what would he do now that winter was coming on?

He felt the dampness on his cheeks as he turned down MacDougal Street toward his apartment. His eyes burned, and he ducked his head as he heard the choking sound in his throat. By the time he crossed Bleeker, the tears were dripping off his chin. When he got to his apartment he collapsed on the bed, fully clothed, and cried him-self to sleep.

–The End —