BY JIMMY IBBOTSON

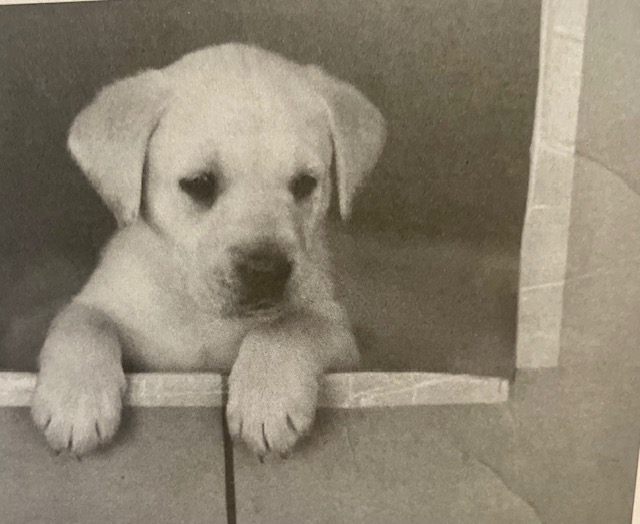

I used to live with the greatest dog. He was a big bull Lab named Nobel Columbo, Scar-Faced Sire of Woody Creek. A big name for a big dog. He was the star of his litter. My eight-year-old son figured it out. He’d sit on the floor for hours, watching the puppies interacting. He’d pick up one or another of the dogs and put them through a series of tests.

He wanted a dog that was comfortable reclining in his arms. What impressed him about the pup he chose was his intrepid spirit. Columbo was the first to circumnavigate the cardboard box of puppy love: eight perfect little squirming, whimpering, sucking, licking and nuzzling highbred hunting dogs. And when my son picked the biggest, whitest male, I didn’t want to talk him out of it.

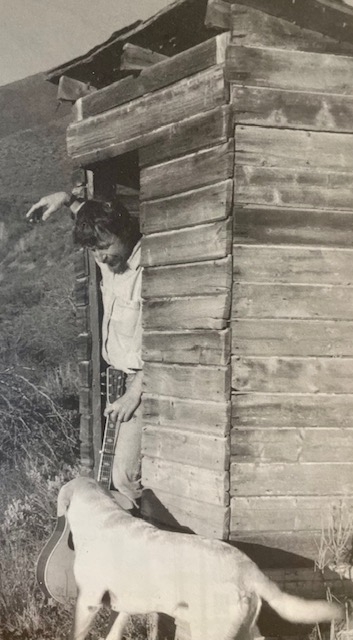

When we moved from Judy Royer’s adobe casita to Unami, my Woody Creek estate, my son and Columbo were working out their relationship. There wasn’t much doubt about it when I was home. The two of them ran roughshod over me. Truth is, we usually had one of his litter mates or progeny with us. His puppies were trouble in the households that got them. I’d get a frantic call and a returned dog. Columbo could usually straighten them out, and the happy family would get a well-trained animal back.

But then there was Guerro, the spitting image of Columbo, out of Maya, his favorite bitch. Guerro had huevos. He was the first to win a game that Columbo loved to play. He’d interest another dog in running around, willy-nilly. The other, usually dumber, animals would get so wrapped up in the joy of Big Bo’s undivided attention that they wouldn’t see the dumpster or fence post. Guerro didn’t play that game. And Guerro became the social director.

My dog had fallen in with a bad crowd. He packed up with his son and rampaged Woody Creek Road. First they mated with every poodle, coyote, or llama that they could charm. Mainly, however, they challenged the mangy mugs of feral canines in the oaken hillsides to sex-charged duels of honor. It was mostly just barking and growling, with the pack of foxes coyotes holding the pure-white, over fed Labs at bay by their sheer number.

But if Bo could get hold of one, he would kick their ass. Trouble was, Guerro had a taste for chicken and pigeon. My neighbor Don Donaldo, polo king of the pamapas, forgave me too quickly. They were his birds that were being slaughtered — some of them beloved Filipino flipping pigeons. So I imposed the harshest sentence on Guerro: he was banned from or house. His outlaw mind would relive his epic days with me and my boy and my dog as he lived out his estrangement from the source of power.

My boy’s mother would get a lot of calls from people in Aspen. Bo would be knocking over their dumpsters, in an effort to recycle barbecue bones and ease the load on the landfill. He was a regular at Rusty’s. He didn’t even have to cross the street to get there.

But Woody Creek was Bo’s domain. When I went on the road or to Mexico, he’d stay up in Snowmass Creek with Maya. But Maya’s owner was then dating Hunter, right next door. By this time, Guerro had found his way back to Maya. So, during evenings of hot tubs and betrayal, Bo and Guerro were forced to find something to occupy themselves at Owl Farm. The peacocks caught their eye and they began plotting ways to mate with the hens.

Hunter tracked me down in a detox center in Cincinnati and cowed the staff into letting me speak with him. “I found that fucking dog of yours, standing on the tail plumage of my favorite peacock, last night. I’m gonna shoot him if you can’t control him.”

I gave him some lame excuse about how much he and Guerro looked like each other, and it was really Guerra’s fault. “Shut up, you mewling drunk,” Hunter growled. “Here’s the deal. One time and one time only, I’ll bounce the buckshot off the snow. But then I’ll use deadly force to protect my birds.”

And that’s what happened. One time and one time only, he bounced the buckshot off the snow. Bo took a handful of the BBs in his loving head. A few creased his forehead and carved a hairless arroyo that never grew back. Hence his name: Noble Columbo, Scar-Faced Sire of Woody Creek. I’d be sitting, idly petting him under a table on the patio at the Tavern, and a BB would fall out of his earflap or forehead. It took years for the last ones to work their way out.

People would ask me about the scar and I’d tell them the story of how he got it. Columbo would sit up tall and listen, making sure that I got it right. Most people would ask if I took revenge on Hunter for shooting such a wonderful pet.

I would tell them that it was the most humane thing that a good neighbor could have done. Columbo never entered Owl Farm again. A neighbor with a smaller sack would have called the cops, and Columbo would have been arrested and I would have been faced with a series of escalating fines. Instead, Columbo continued to prowl the neighborhood, charming the kids at the Community School out of their lunches and falling into a sunny senility around the old painter and the girls in the garden.